Villamor, Jesus A.

GS, HS 1932, ACS 1936

DECEASED

2007

DLSAA Distinguished Lasallian Awardee

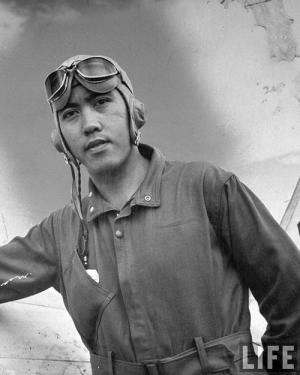

The outstanding Filipino hero of the last World War was JESUS VILLAMoR (HS 32) who was the first aviator to shoot down a Japanese plane in a dogfight on December 10, 1941. Although born in Manila, Jess was of Ilocano parentage. His father, Ignacio Villamor, jurist and first Filipino president of the University of the Philippines, had distinguished himself as a scholar. Jess was born on November 9, 1911, and enrolled in the kindergarten class of La Salle where his two older brothers, Jose (HS ‘25) and Florencio (HS ‘26), were then studying. His first hour in school terrified him, for he started bawling until one of the amahs comforted him. His teacher, the benign Juan Medrano, soothed him. “Far from being outraged by my impertinence,” Jess later wrote in his autobiography, “Medrano was impressed. Surely, he

felt, something would come out of such a presumptuous soul.” As a high school student, he dreamt of becoming an aviator; so after graduation, and after taking some preliminary courses at the Philippine Air Taxi Company, he prevailed upon his parents to send him to Dallas, Texas, where he secured a license as a transport pilot. Later, he found to his chagrin that the license was not a recommendation for a flying job. So back to Manila he went, and back to La Salle for his Associate in Arts degree, a requisite before he could apply for a commission in the fledging air corps of the Philippine Army. Once a probationary 3rd lieutenant in 1936, he was ordered for further training to Randolph Field, the U.S. Air Force base in San Antonio, Texas. His American brother officers nicknamed him “Little Chief Oompah” because he was the smallest member of his class. Two years later he was back in Manila, cocksure that he could beat any flier that the enemy could field. He was promoted to captain and made commander of the PAC flying school at Zablan Field, at the outskirts of then Camp Murphy. On December 10, two days after the declaration of war in the Pacific, the crucial test came. Mitsubishi two-engined bombers, escorted by squadrons of fighter planes, flew over Clark Field, Manila and Cavite with impunity. At 10 o'clock that morning along with other pilots Jess scrambled to the seat of his outmoded P-26 to contest the enemy's superiority in the air. At 5,000 feet he suddenly discovered that a Zero was chasing him. No matter how he maneuvered his plane, the Zero tailed him. Frantically, he tried to shake the Zero, but whatever he did the Zero did better, faster and easier. “I cursed myself for having so underrated the Japanese,” he admitted afterwards. Suddenly, the Zero appeared in front of him. Just in the split second before the enemy pilot tried to avoid a head-on collision, Jess squeezed the gun-trigger. The .30 caliber armor-piercing incendiary bullets of his Boeing plane tore the wings of the Zero, which plunged into a fiery death over Marikina Valley. Suddenly the other Zeros flew away without having downed a single P-26. “How was it, Villamor?” asked General Basilio Valdes, chief of staff, who had driven to the airdrome. “Were you scared?” “Yes, sir,” replied Jess. “I was very scared.” For that heroic encounter, Villamor was personally awarded the Distinguished Service Cross with an oak leaf cluster by Geneal Douglas MacArthur, “for unbelievable courage in leading his tiny squadron of antiquated P-26s for the December 10 and 12 aerial engagements against the enemy.” His picture was splashed on all the front pages of newspapers and magazines. He had become the first Filipino hero of the war. While in Bataan he was ordered to pilot an observation plane over Ternate, Cavite, where the Japanese had mounted large guns to batter the island of Corregidor. Although hidden from ground view, they were plainly visible from the air. Corregidor's big mortars quickly silenced the enemy's artillery.

He managed to leave Bataan on a PT boat before Bataan fell, then hitched a plane ride to Australia. The Allied Intelligence Bureau (AIB) chose him to head an espionage group to the Visayas. He landed in southern Negros late in 1942. His job was to establish a network of military intelligence, and with a hand-operated radio transmitter he made his reports to MacArthur's headquarters in Brisbane, northwestern Australia. The underground resistance throughout the islands was in a mess, with leaders vying for power and often fighting with one another. He succeeded in untangling the disorder in Negros before he was called back to Australia six months later. For some reason not clear to this day, he was “put on a shelf” and sent on futile missions to the United States. Apparently, he had earned the dislike of the chief of MacArthur's staff, General Richard Sutherland. Col. Courtney Whitney decided to abolish the AIB, and assign only Americans to lead espionage missions to the islands.

Jess Villamor returned to Manila after the war to be named administrator of the Civil Aeronautic Board of the independent Philippine government, but resigned to return to the United States in 1948 as a consultant of the U.S. CAB. As an American citizen he returned to military aviation during the Korean war, and became an agent of the Central Intelligence Agency during the Vietnam war.

In September 1971 he was rushed to Georgetown University Hospital, gravely ill. He had a cancerous tumor in his right lung. Two weeks later, on October 28, he died, and his remains were flown back to Makati where he was buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani (Cemetery of Heroes). The first war hero of the Philippines a La Sallite, had passed into history.